Being single is hard enough without these pejoratives.

September 14, 2017

On this day in 2005, England and Wales stopped using the terms “bachelor” and “spinster” to describe unmarried people on official documents, as they had done for decades prior. “As part of the Civil Partnership Act, these somewhat quaint terms will make way for a new catch-all description for unmarried men and women: ‘single,’” the BBC wrote at the time. By the time these terms were replaced, it wrote, they’d both become antiquated. But where did they come from in the first place?

Bachelor

The Oxford English Dictionary’s first recorded use of the word “bachelor” to mean an unmarried man came around 1386, with Geoffrey Chaucer. In one of the stories in The Canterbury Tales, the about twenty-year-old squire is described as “a lover and lively bachelor” who spends time chasing the ladies, partying and jousting, and who barely sleeps.

Before that, according to Merriam-Webster, bachelor (or, earlier, bacheler) referred to a young man, especially one who held a bachelor’s degree or followed a knight as his squire. But as Chaucer’s partying squire shows, both meanings were relatively positive.

“Bachelor” still makes regular appearances: think bachelor and bachelorette parties, The Bachelor and even biology, which refers to unpaired male animals as “bachelor.”

Spinster

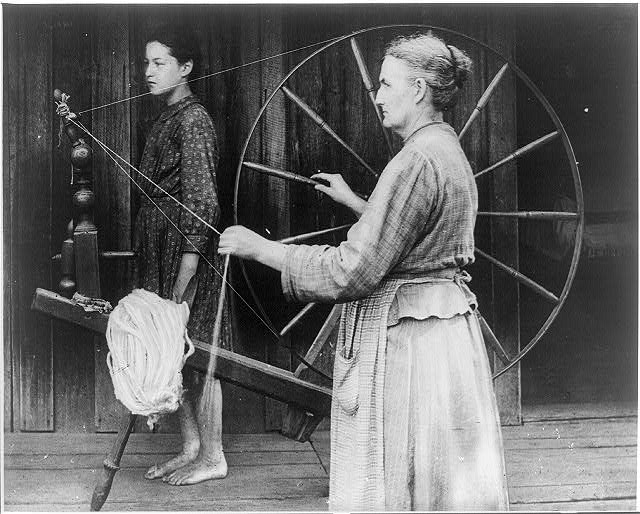

Spinster, however, has other associations in the popular discourse, although the word entered the English language around the same time as bachelor. It was first used in the mid-1300s, though then it literally meant “woman who spins for a living.”

In an age where all clothing had to be made by hand and women were empowered as part of guilds, being a spinster wasn’t a bad thing. But the meaning changed over time. “Some scholars suggest that during the late Middle Ages, married tradeswomen had greater access to raw materials and the market (through their husbands) than unmarried women did, and therefore unmarried women ended up with lower-status, lower-income jobs like combing, carding and spinning wool,” writes Merriam-Webster. “These jobs didn’t require access to expensive tools like looms and could be done at home.”

By the seventeenth century, writes author Naomi Braun Rosenthal, the word “spinster” had come to hold its common association of an unmarried woman. However, “it was not until the eighteenth century that the term ‘spinster’ became synonymous with the equally ancient, but considerably less neutral appelation, ‘old maid,’ she writes.”

Cat lady. Old maid. “Spinster of this parish.” This language was used to dismiss women who were past an age where it was deemed appropriate for them to be married. In the words of Jane Austen about her character Charlotte Lucas, who at 27 was well on her way to being a spinster, “Without thinking highly either of men or of matrimony, marriage had always been her object; it was the only honourable provision for well-educated young women of small fortune, and however uncertain of giving happiness, must be their pleasantest preservative from want.”

But as Erin Blakemore writes for JStor Daily, the word has been used to “deride and marginalize women who remain single.” “There is no such thing as an ‘eligible spinster,’” wrote scholar M. Strauss-Noll. While the continued use of "bachelor" demonstrates the opportunity presented by that word–an “eligible bachelor” can choose who to marry–"spinster" demonstrates how many opportunities were unavailable to unmarried women in the West.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.